There was a time when I wondered how twentysomething radicals turned into straitlaced middle-aged professionals with fond but fuzzy memories of those old days.

Now, at 28, I know.

It’s not just that I’m comfortable now, with my granite countertops and savings account and nice white professional friends—though of course that’s part of it. Of course those things are strangely seductive; however silly they seem listed out there in black and white, I cling to pretty, to safe, without even realizing it.

But that’s not really why I’m tempted to quit. It’s because—as much freedom and joy as getting older brings—I also see how small I am now, and how big the problems are. It’s because burnout is real. It’s because the powers-that-be seem unbeatable, and because I’ve made so many mistakes, and because unlearning and relearning and letting go and starting over are so very tiring. I often think I will be beaten—not by pain or adversity, because these can be used as galvanizing forces; instead, I often think I will be beaten by simple exhaustion.

I see now how you can start to get woke, but slowly drift on back to sleep.

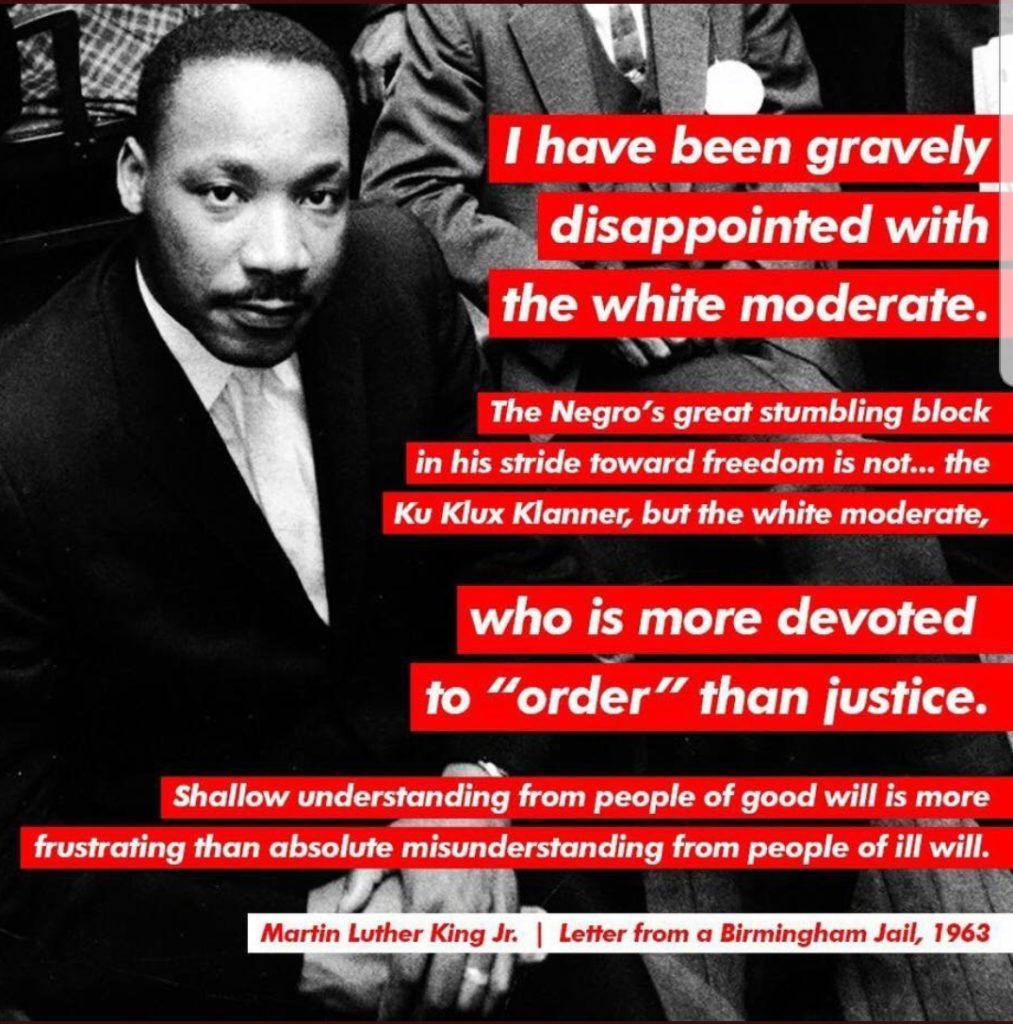

We grew up learning about the nice Dr. King, not the woke Dr. King. In the process our schools martyred him over and over—by silencing his radical voice, turning him into a vague inspirational figure, and pretending his death meant more than his life.

Some of us cherry-pick our own issues to apply his quote to: “injustice everywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” We fail to admit what he was really saying:

NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE.

The truth is, 75% of whites had an unfavorable opinion of Dr. King when he was assassinated for the second time, and killed. He disrupted the status quo, and that made him dangerous. He told the truth, and the truth set people free, and that made him dangerous. He loved them enough to stand for justice, and that made him dangerous.

In the Bible, “peace” (shalom) is not the absence of conflict, but the presence of right relationship between all beings. Over and over, we see God bringing peace through an unsettling—even violent—reckoning with evil. Intentional *and* unintentional evil. Personal *and* systemic sin.

And this is good news! If peace is not an absence but the presence of God’s Spirit making things right, then peace is not something we can only wish for; it is something we can become.

If I am not beaten by simple exhaustion—if someone stronger and wiser rises from the embers of my burned-out striving self—it will be because I learned, somehow, like Dr. King, to pray.

To live and work out of something other than guilt, or anger, or fear, or self-righteousness.

To listen and follow, listen and follow, Spirit’s voice spoken by the marginalized.

To sit down in my spirit with the Spirit, and one day at a time to do what is right, however confounding it is to the outside world.

However dangerous they say we are.

To embody a supernatural and immoveable peace.

All-loving God, who was named by Hagar ‘the God who sees’ in the midst of her oppression; see us now in our anger, fear, grief, and need.

All-loving God, who was named by Hagar ‘the God who sees’ in the midst of her oppression; see us now in our anger, fear, grief, and need.

Dear Lyndsey…

Dear Lyndsey… I think if you knew what others pay for your attention, you might covet it more, yourself.

I think if you knew what others pay for your attention, you might covet it more, yourself. The middle school locker room. The other 99% of the day, I could generally pretend not to have a body, but in the fluorescent seventh-grade gym, there we all just…were. I remember my routine: find a corner, try to shrink, change as fast as possible, wear an indifferent face so no one will think you’re a baby. Make an exit. Breathe again.

The middle school locker room. The other 99% of the day, I could generally pretend not to have a body, but in the fluorescent seventh-grade gym, there we all just…were. I remember my routine: find a corner, try to shrink, change as fast as possible, wear an indifferent face so no one will think you’re a baby. Make an exit. Breathe again.