I heard the truth about my town in Georgia—home base since I was 13—over the radio, from a woman in Philadelphia. It was a Terry Gross interview with the author of a book released last summer about the history of Forsyth County. Maybe it was a run-of-the-mill interview, sometimes even if you’re a Terry fan they’re a little boring, but to me it was bizarre and hurtful and fascinating and horrible all at the same time: hearing a man’s voice in the little car speakers reciting the details of two lynchings that took place on the town square where I had purchased a marriage license two months before.

To be more precise, it was all of those things after the fact, because my response to overwhelming awful things is always immediate dissociation. At the time, I thought mostly of the classrooms two blocks from that square, where they’d taught us about the formation of the KKK on Stone Mountain but not about the lynchings in our town. Not about the weeks after the lynchings when every black person in the county was driven out of their homes. Not about the family that tried to quietly return and woke up to dynamite under their house. Not about the fact that there’s no record of who survived and who didn’t.

There were rumors, of course, about whose fault it might be that our county, even in the 2000s, held far fewer black people than any other in Georgia despite its rapid growth: a few white hoods in the 60s, a sign warning black people out before sundown. But those rumors held no lynchings and no expulsions by night riders and certainly no mention of the massive protest in the 80s, residents demanding they be allowed to keep their county white.

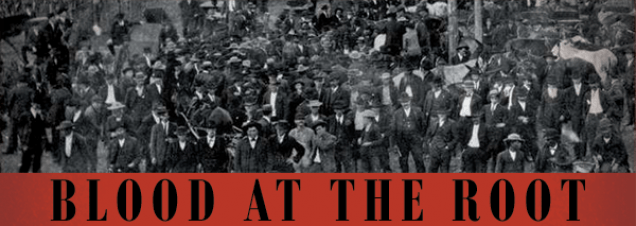

In December I wrapped gifts, packed an enormous duffel bag, and in the last second before leaving Charleston for home I downloaded the book. It’s a quick read, really just a chronological telling of events. I’d expected a bit more from it—a primer on how to feel or what to do would have been nice. Instead, there were the happenings, then the end; and then I wandered about the county, visiting friends and the Dairy Queen downtown, in a state of surreality, seeing the 1910s superimposed over every place that composed my beloved home. The stolen homesteads of freed slaves forgotten beneath stately churches; the site of the rally, now some of the county’s most valuable retail real estate; and always, the lynchings of teenagers in the square.

I don’t know if it is merely naive or some much more serious moral and imaginative failing, but it was one thing to know of lynchings somewhere in those mountains, and another thing to stare down a picture of one across the street from Sal’s pizza place. It was one thing to hear rumors that black people had been unwelcome on our streets long ago, but another to read with what inhuman ferociousness their absence had been enforced up until my own lifetime.

I have not spoken much about all this. I am just beginning to grieve the place I thought I knew.

Even when we speak about the importance of history, we often act as though it is a collection of case studies that might sometime offer useful analogies to our own time, rather than recognizing that it is a part of us. We are learning every day, too, that this is no metaphor, our very selves shaped by history: trauma is passed on through human DNA as surely as injustice is passed on through our institutions. It is the privileged who study history; it is the oppressed who remember it. I came to adulthood asking why so much is wrong with the world. Those who bear the brunt of the wrong have always known.

And at the same time that it’s easy, once you start, to trace the series of events leading my people to have things so much easier than others, it’s impossible to quantify my own individual part in any of it. It’s nothing: I never asked or hoped for things to be this way any more than the victims did. And it’s infinite: my family came to Forsyth for its peace, prosperity, and Good Schools, all of which were uniquely available because of the county’s history and uniquely available to us.

It is crass to speak of quantifying such things anyway. But, I think, even the sagest of “woke white people” can unknowingly hope to do so, as if that might be the first step to erasing the hurt. In the interview through the car speakers, I recognized a certain instinct in the book’s author: a desire for absolution. As weeks went by and I tunneled down into my own distress, I found at the root of the pit in my stomach was an absurd hope: maybe if I do enough, or give enough up to others, I can become innocent of this.

But none of us will ever be innocent of it.

The Bible speaks often of communal sin. This, like most things in the Bible, is inconvenient, if not incomprehensible, to the individualistic myths that make up the American way. Some well-meaning people who have worked very hard not to commit sins will probably always refuse to comprehend it, protecting instead the idea of their self-made virtue. In so doing, they will refuse to understand the basic fabric of the world and perhaps of God: that we all belong to one another. We can’t stand up a self unattached to the others who remake us every day, any more than the squares of a quilt can be without the others.

I don’t know how anyone makes sense of history and its injustices without feeling this fabric under their fingers.

The Bible also speaks often of communal redemption. Thanks be to God, the un-innocent belong at the family table.

Now I live in a city that has prospered from the products of slavery since its inception three hundred and fifty years ago. We are still getting to know one another, so I cannot say much about what, exactly, this means for Charleston. But I can say that the city will never become innocent of the shooting at Mother Emanuel, certainly not by deeming a single life valueless and then offering that warped nothing as if it could be a sacrifice to justice.

Everyone is angry at Dylann Roof, but behind the anger lies fear: fear that he might be one of us. To entertain the idea of Roof in prison for life is to imagine him as something other than a monster that must be put down. It is to face the fact that a man, mentally sound enough to represent himself at trial, found little evidence in the society around him to dissuade him from the racist alternate reality he’d chosen. That man believed he could start a race war by carrying out his crime in the right city: what was once a city of enslaved people, ruled by a fearful and violent minority of white men.

Perhaps the victims and their families should be the ones to sentence Dylann Roof, but they are not. And we all sit in silent judgment of him: a jury of his peers. To leave Roof alive would be painful, to say the least. It would inspire justified outrage on several fronts. But to kill him means to label him irredeemable, while somehow maintaining that we are not. That is false. By killing him, instead, we further damn ourselves in the belief that the history that inspired Roof can be purged by wiping him out.

To leave Roof alive would be to look into his hate-filled face and force ourselves to recognize the fear, supremacy, and violence that every day enslave us all. Only when we stop settling for the scapegoat will we finally reach the beginning of our own repentance.